| It’s an all too common experience for anyone who’s

ever traveled outside the United States – whether ministering to the

poor or studying in an international setting, the cultural differences

experienced abroad can be eye opening to world travelers. But the

challenges experienced in another country such as different foods or

different social customs can sometimes pale in comparison to the

emotions felt on the return trip.

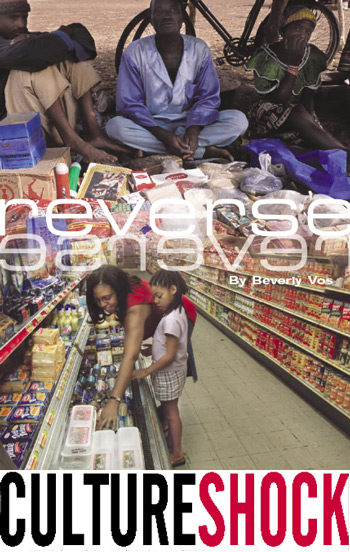

Back on American soil, reverse culture shock can quickly set in, causing those returning to view their own way of life with a new perspective, often feeling disconnected to a land they call home. Compared to most countries of the world, life in the United States is like no other place on the planet. American citizens have wealth, excess, privileges, opportunities, access, choices, and nearly unlimited resources. However, sometimes the contrast is too great and upon re-entry, those returning from another country may experience restlessness, negativity, uncertainty, or even loneliness. The freedom of plenty – and the responsibility “When the customs agent welcomed me home, I thought how wonderful those words sounded,” says Cossiboom, recalling how excited he was to be back on his own country’s soil and the patriotism he felt at the sight of American flags flying. But in contrast with his recent witness to the hardships of displaced people from a country currently at war with the U.S, the freedom he felt on his return also had a harshness to it. “I’ve definitely become fully aware of the plight of people who are suffering all over the world,” says Cossiboom. “As American citizens, we enjoy rights and privileges and we fight to preserve and defend those freedoms. But I think the challenge is to view ourselves as world citizens who have the responsibility to recognize injustices and oppression and fight to defend the dignity of all people.” Cossiboom understands that this feeling is something he must work through and allow its outcome to broaden his understanding of the world. After having served in China, the Philippines and Italy, he feels more aware of what others have to offer. He encourages his friends in America to have sensitivity to other cultures and people. “We have much but that doesn’t necessarily mean we are the best.” Called to serve, abroad and at home Students on short-term assignments, just like career missionaries, are purposefully prepared for the culture they are entering. They are told what they will see and experience and they understand the poverty and impoverished conditions they will see as well as the lack of many modern conveniences. They go, however, because they are called to serve and to give of themselves to others. A global experience is new and adventuresome as well as exhausting and eye opening – and the return trip can be just as rich in new understandings. When Union alumni Patrick (’87) and Lana (‘90) Beard and their children returned to the U.S. from their ministry in Ethiopia, they were shocked at how much excess and waste there seemed to be, in a country where they had given little thought of waste before leaving for overseas. “Just going into a store and seeing an entire aisle of breakfast cereal was amazing,” says Patrick Beard. “We were literally stunned – we couldn’t make a simple decision with so many choices.” Beard also recalls going to a buffet restaurant shortly after the family’s return and being totally unprepared for the sight of diners with heaping plates of food, going back for more and more – meals that back in Ethiopia could have lasted weeks if not months. “Other people groups don’t resent us because we are free, rich, or even Christian,” believes Beard. “Instead, I think they are appalled at our gluttony. It takes honesty to assess ourselves and find the balance in living responsibly within a culture.” Cammie Vos Johnson (’97) spent a year in the Czech Republic tutoring missionary children. For her, returning to the States was not difficult, however, she believes Prague is still the only place for which she has ever felt a homesickness. She liked the simpler and slower pace. “They don’t seem to need the excesses and stuff that we seem to need in the U.S,” says Johnson. “The people are more reserved and softer in contrast to our stereotype of loud and energetic Americans.” After several years at home again, she says the experience has still brought a change in her life and has helped develop her character more fully. Union student Lauren Webb, junior chemistry major, served in Venezuela for several months and found that she was prepared and ready to come home. She felt deeply blessed by all the opportunities to serve. For her, culture shock was going – not returning. “I’m thankful for what we have in the U.S. —it’s not just the cars, conveniences and l uxuries,” says Webb. “My appreciation has really deepened for things like the opportunities to achieve and succeed.” Webb’s desire is to return to foreign fields as a medical missionary. She feels she gained much more from her experience than what she gave and maintains the most important lesson in re-entry is to keep what was learned. “It is imperative to never give away the place that country has gained in your heart,” stresses Webb. “Continue to faithfully pray for the people and their needs and rejoice in all that God has done.” The challenge for those who return home and for the ones who hear their message is to gain an understanding and balance of who we are as citizens of the world or more importantly as citizens of the Kingdom, says Beard. He offers insight into this by pointing out that no culture—in our own country or in foreign countries—is all good or all bad. “In making an honest assessment of our own selves and culture, we acknowledge that every culture in the world opposes God,” says Beard. “The good message for all people is that God, in his grace, works restoration through Christ.” |