|

||||

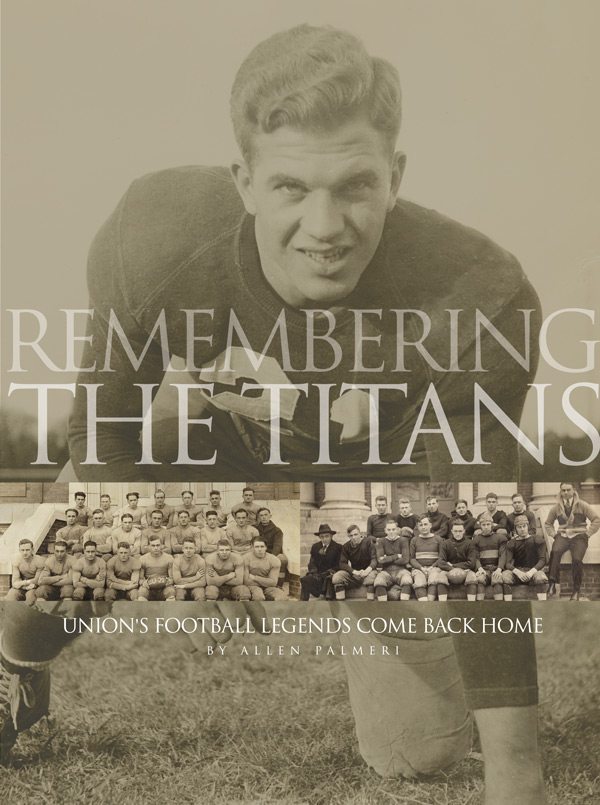

| Near the end, when victories

were as hard to come by as creeks in the desert, Robert Jelks learned to

appreciate every gridiron success as head coach of the Union University

football team.

In 1951, the Bulldogs won one game. In 1952, they won three. In 1953, Union chose to disband its football program. Jelks, who also played for Union back in the 1930s, has stood tall through the years as the last head football coach the Bulldogs have ever had. “That was my life,” said Jelks, 88, who now runs an insurance agency with his son in Paris, Tenn. “That’s how much I enjoyed it.” Union’s teams were more successful when Jelks was a player back in 1936 and 1937. Times had changed by the time he took over as coach. “I enjoyed coaching the boys,” he said. “I had a bunch of fine fellows playing. We just didn’t have the size. All these teams that we used to beat when I was playing - like Murray State, Middle Tennessee, East Tennessee State, Florence, Alabama - a lot of those teams, we just wore them down.” Jelks had been a high school coach for 14 years before taking over the helm at Union. He remembers some of that high school coaching experience coming into play in a 40-0 defeat of the University of Tennessee-Martin. “That was the first one we won the second year I was at Union,” he said. “Union was playing against some boys I had coached up at Grove High School in Paris. There were about five of them on that UT team. They were going to take us in, but they didn’t have that pleasure.” On the very first play, David “Squirt” Miller ran about 55 or 60 yards for a touchdown, and the Bulldogs were off to the races. “They were expecting us to shift into a single wing, which we had used at Grove High School, and we ran a T formation on them.” Another satisfying victory in that last season of football came against Georgetown, Ky., 14-6. But the most satisfying win still has a special place in his heart -- a win that made a little bit of history.

“The one I enjoyed the most was beating Southwestern out of Memphis, which is now Rhodes College. We had never beaten them in the history of Union until that night. We laid it on them 35-0.” Jelks and another former Union player, 87-year-old Roy Thompson, remember when legendary coach Paul W. “Bear” Bryant came to Union to get his start as an assistant coach under A.B. Hollingsworth. Bryant, who was only one year removed from playing in the Rose Bowl for the University of Alabama, conducted some spring training drills in 1936 at Union before going back to Alabama to serve as an assistant coach under Frank Thomas. Bryant went on to put together a career coaching record of 323-85-17, with six national championships. “I have said many times that I was probably the smallest second-string quarterback that Bear Bryant ever coached,” Thompson said. At 5-foot-5 and 135 pounds, Thompson knew beyond a doubt that he had to rely on his blockers. Once, against a Middle Tennessee team that outweighed Union along the line, he experienced a career highlight. “I remember in that particular game I was able to score on a quarterback sneak,” Thompson said. “There was a left tackle named R.L. Ammonds. In the huddle after I called the play, Ammonds says, ‘Follow me.’ So I stepped to the left and took the ball -- it wasn’t but a yard or two -- and R.L. took me right on in for a touchdown.” Thompson just missed being a part of the Union team that went down to Mexico City to play a game in 1934. His older brother, Francis, was part of the team that beat the University of Mexico 32-6 before 10,000 fans. Back then the Bulldogs weren’t afraid to take on the larger schools. Jelks, who played both ways as an end, remembered holding Ole Miss scoreless in the first half before “they poured it on us in the second half.” Thompson recalled a trip to Nashville to play Vanderbilt in the first game of the year. “I’m sure that it was Vanderbilt’s warmup game that they used to try to have, and at halftime we held them with one touchdown, I believe, or maybe we were tied with them,” Thompson said. “Coach was real pleased with our playing there, but they came back and scored two or three touchdowns in the second half. That was real nice playing in that big stadium. We thought we were head and shoulders above anybody.” The tradition of Union playing schools that were noted for playing on the top level of college football continued into the 1940s, when end and three-year co-captain Buford Matlock played. “I really enjoyed it,” said Matlock, who started every game but one from 1946-1949, “We had a good group of players, but the schedule was a little hard back then. We had to play larger state schools like Chattanooga, Mississippi Southern, Louisville, teams like that, so we didn’t have quite as good a record as we would have liked to have had. “One year against Memphis State, they could have broken the record for scoring in a year if they made 40 something points, but we held them down to something like 25. They didn’t make it.” His teammate for three of those seasons, Bill Gregory, remembered how a lot of positive things came together in 1947, when the Bulldogs finished 5-5. “It was just determination, I guess. And we had fun.” Gregory was a 6-foot, 150-pound end who remembers the day when Chattanooga “beat the stew out of us” 35-0. Other than that, though, the Bulldogs were competitive. One game at Mississippi Southern stands out as an example. “The week before they had beaten Alabama, and the week before that they tied Auburn,” Gregory said. “Of course we were far outclassed, but luckily it just poured down rain that night. I mean we had a cloudburst. They beat us by three touchdowns. “The rain was so bad and it got so muddy, the only way you could tell one team from the other was we had red helmets and they had black ones. You tackled every black helmet you saw. Literally the referee had to hold his foot on the ball to keep it from floating off. That’s how deep the water was on the field. It rained the whole time that we played.” Jelks, Thompson, Matlock and Gregory were used to one-platoon football, when a player had to stay on the field and learn whatever skills and techniques it took to play both offense and defense. Today’s brand of college football seems foreign to them. “It was played by men back then,” Gregory said. “Now it’s played by a bunch of kids. They don’t even have to be in shape to play ball now because they just play one way. They go out and play three plays then come in and sit down in front of a fan.” But some of Union’s former players complimented the modern starts of the gridiron. Added Thompson, “The boys now are so much larger, and they’re in excellent shape, hard hitters. I’m not sure that I could play today. However, I don’t think that I ever came up on an opposing player that I thought that I couldn’t take down with a block. I never did fear them, anyway.”

The level of seriousness that has come to characterize the major college football of today just was not there in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. Union’s football players showed up and played hard, but if they lost it was not the end of the world. “Back then, you didn’t have all the assistant coaches, and you didn’t have films of the game to study, the opponents’ films and things like that that they have today,” Matlock said. “It was more fun back then because there wasn’t as much pressure put on the players to win.” Pressure was World War II. When players like Matlock and Gregory made it back alive, they were thrilled to be able to play a game like football. “We just went out and had a big time,” Gregory said. “It wasn’t a life-or-death thing. Most of the boys who played when I did were all veterans. We’d been in the Navy, the Army and the Marines for three or four years before we went to Union. I went right out of high school into the Navy. I was in the Pacific for two years, so coming back playing football was a breeze.” Football has become much more sophisticated in the 21st century, particularly in the passing game. Union’s offense in the late 1940s consisted mainly of the single wing and double wing formations, which emphasized trickery in the backfield. Ends like Matlock and Gregory were mostly there to block. “We had maybe four or five pass plays,” Gregory said. “If we threw 10 times a game it was unusual. Now they throw every other down, so it’s a different game. The plays are so much more complicated now because they’ve got specialists playing at every position.” Thompson remembered back to the day when the university installed lights on the field. It took the Union backs some time to adjust. “We thought it was really a disadvantage to try to receive punts in the lights that we had, because the ball would go up out of sight and then appear to be falling.” Thompson has 64 reasons to look back fondly on his days at Union. Those are the years that he has been married to Verna, whom he met on campus. Retired now in Ripley, Tenn., he remembered how much of an impact his days in the Union football program have had on his life. “Staying with it and knowing that things didn’t come easy, that you had to work hard and you had to train for it, you had to put your mind to it,” he said. “We did this, and I think that has followed throughout life. If you are assigned a job, stick with it and work at it until you get the job done to your satisfaction.” Matlock, who is retired in Jackson, said that football made his life a lot easier. “I learned to get along with people, learned to take the low spots as well as the high spots in life.” Gregory, who owns a sign painting business in Jackson, looks back on “the appreciation of playing with the people we played with, the friendships we’ve kept up through the years, and just the camaraderie, I guess.” Camaraderie would be the right word to choose. Union’s football players used to have to maintain a pretty high degree of closeness when it came to one particular piece of equipment. “We had probably 45 or 50 players on the team and we only had about 25 or 30 helmets,” Gregory said. “They didn’t spend a lot of money on equipment. Now, by the time these kids put their gloves on and their elbow pads on and their shin guards and everything else, they can’t play ball. They’ve got too much stuff on. They can’t even move.” The recent reunion of former Union football players at the university was deeply appreciated by a distinguished group of gentlemen who are now more than 50 years removed from their playing days. “I thought it was great,” Jelks said. “It was so good to see so many of those boys I had the privilege of coaching that I hadn’t seen since those days.” “Very nice,” Thompson said. “We appreciated being recognized as old football players. That was something that we never in our lifetime expected to be called back at this late age and recognized.” The special nature of the reunion hit home with Gregory. “I thought it was nice,” he said. “That was real good. We have had several football reunions, but this was the last one, I guess, so it was probably the best.” Palmeri is the former editor of Share the Victory, the national sports magazine for Fellowship of Christian Athletes. You may write to him at unionite@uu.edu. |