|

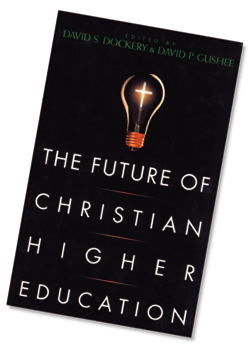

by Barbara McMillin In describing the liberal arts education provided by the early Puritan colleges, Christian scholar and revered Wheaton College professor Arthur F. Holmes uses the phrase “eloquent wisdom.” Such a phrase proves to be an apt description of the collection of addresses edited by Union President David S. Dockery and Associate Professor of Christian Studies David P. Gushee. The Future of Christian Higher Education, published by Broadman & Holman and released in June of 1999, features addresses by eighteen of the nation’s top Christian educators. Originally delivered as either chapel, convocation, or commencement addresses or lectures, each piece confirms that the future of Christian higher education is bright. Though the essays reflect a broad range of styles and formats, the text displays a “thematic continuity focused on the needs, purposes, mission, direction, and challenges of Christian higher education as we move into the twenty-first century.” As Joel Carpenter explains, a primary need is for Christian colleges and universities to recognize and combat the historical trend toward secularization in American higher education. Furthermore, not only must we learn from the past, but we must embrace a willingness to be what Dockery calls “future-directed.” As we look toward the future, we must underscore the integral role of the faculty. These professors must display what Gushee calls “authentic piety, covenant fidelity, critical curiosity, transformative engagement, and purposeful self-discipline.” Karen A. Longman proposes that Christian educators need to dream of and ultimately realize new ways to help students succeed, to affirm giftedness, to open up the world for our students, to utilize the best of technology, and to develop exceptional faculty. As Dockery explains in the introduction, our purpose must be to “keep Christian higher education distinctively Christian.” He adds: “At this time we must take seriously the call to develop Christian minds. The tensions often created between academic excellence and piety, between scholarship and teaching, between academic pursuits and revealed truth, between the academy and the church, will always be with us. “But we can only address these challenges and bridge the tensions with both-and answers. Either-or dichotomies will not advance the cause of Christian higher education at this kairos moment. The issues of truth, the call to teach and mentor, and the vision to think and live Christianly are at this time our highest priorities. “To achieve these priorities, we must do as Kenneth G. Elzinga encourages--and that is to ‘take every thought captive to Christ’.” Arthur F. Holmes concludes that such a commitment will enable Christian higher education to develop character and to integrate faith and learning, while at once confirming the usefulness of a liberal education. Stan D. Gaede focuses on the challenge of how to “discover and embrace different kinds of diversity,” while resisting the diversity that results in a “philosophical vacuum.” That Dockery, Norm Sonju, Millard J. Erickson, and Harry L. Poe all focus on the implications of postmodern thought confirms that the greatest challenge facing Christian higher education is responding to a culture that fails to recognize the existence of absolute truth. The Future of Christian Higher Education does indeed abound with eloquent wisdom–wisdom for faculty and administrators who have responded to God’s call to service in Christian higher education; wisdom for parents who seek to guide their college-bound children toward a place where faith and learning are truly one; and wisdom for graduates of Christian colleges and universities who desire to support their alma mater with their prayers and resources. Such wisdom is a necessity, for, as David Gushee concludes, we must be about the business of “preserving our souls . . . while advancing our minds.” |

New volume addresses future of Christian colleges

New volume addresses future of Christian colleges